I am headed to a conference in Seattle the day after tomorrow and striving desperately to catch up on things before I go (I am behind on every imaginable project). So thank goodness that for this week’s #HMWYBS Nathaniel selected a package feature — Vittorio De Sica’s Yesterday, Today, and Tomorrow (1963). Since I was in a hurry, I screened only the short middle film, “Anna,” but I loved it and am looking forward to seeing how it works with the other segments when I have the chance to watch them.

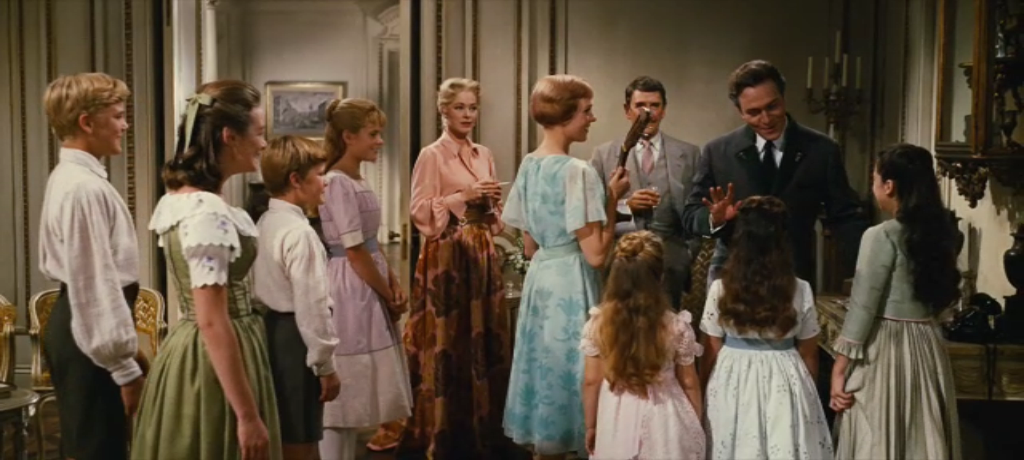

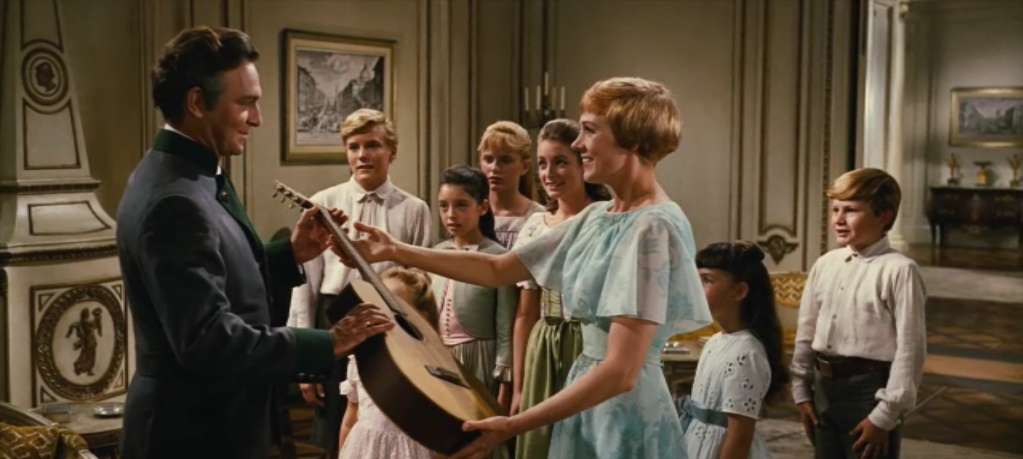

The majority of the movie takes place in Anna (Sophia Loren)’s Rolls-Royce. She is the bored wife of a wealthy businessman, and she takes pleasure in using the supremely expensive car to punish men for not living up to her expectations. The husband is out of town, so she takes it to fetch her lover, Renzo (Marcello Mastroianni), for a jaunt around town. When Renzo swerves the car into a tractor and reveals that he isn’t “man” enough to get it going again, she uses the accident (and Renzo’s incompetence) to hook literally the next man (Armando Trovajoli) that drives by. Anna is a terrible driver, nearly running over every person in sight and deliberately crashing into a number of bumpers. She is Cruella De Ville but more interested in skinning men than puppies.

The whole film is lovely, and I screen-grabbed several shots of the two lovers driving around town. Giuseppe Rotuno’s camera roams around the car, sometimes sitting in the backseat, sometimes looking in from the exterior, but always contributing to the film’s tension and excitement. I particularly admired the shots utilizing the car’s windows either to signal the disconnect between the characters’ points of view (see the image below) or to lend a dreamy/cloudy quality to the fantasy Anna concocts about running away from her wealthy husband to live a life of relative poverty and simplicity with the Mastroianni character (see the image at the top of this post).

But my “best” post from the sequence is the last one. Anna and the man she eventually runs away with have talked cars throughout the previous scene, but to Renzo, who has been looking on from the other side of the road, it is abundantly clear that he is being traded in (like a car — get it?). After Anna drives off on the other man’s luxury wheels, speeding by him with her hand out the window in a dismissive gesture, Renzo buys a bouquet of flowers and heads back into town. The colors are gorgeous, with the white lines created by the guardrail and the painted median converging on the wrecked vehicle in the background. Whatever dreams Renzo has had of running off with Anna are smoldering behind him, but his dejected frown releases into a boyish grin. Suddenly, it dawns on all of us that his is a happy ending. The crash behind him is a mere scrape compared to the pain that would have awaited him in an even longer relationship with the feisty socialite Anna.