To address whether different game genres require different considerations for where their sense of agency lies between the two poles of schema and image, I’ll be taking a look at fighting games like Street Fighter and Super Smash Bros. and then comparing these to action-roleplaying games such as The Witcher 3: Wild Hunt and Bioshock.

In Super Smash Bros. and Street Fighter, the gameplay is driven towards the pole of body schema. The controls for the fighters are mapped to a gamepad and the movements required to play the game rate very low on the complexity of P-actions when taken individually. A P-action will punch, kick, grab, block, jump, or perform some other similar action that involve an input of direction and the action desired. This said, a string of P-actions performed in quick succession correctly can send a grown adult home crying to their parents because your anthropomorphic fox fighting avatar unleashed a flurry of millisecond-fast destruction on to their Italian plumber fighting avatar, thus winning you a competition and roughly $10,000 prize money. These are real things that happen.

Now, the rapidity of translation of action input and action output makes these games extremely fast-paced despite the apparent simplicity of the game itself. This competitive game format combined with a high skill cap often means that the agency of the player resides within their sensory-motor capacities and whether they can respond both quickly and correctly to changing situations while in virtual combat with another player. The responses must be simultaneously consciously considered and automatic, which definitely downplays the importance of body image in these fighting games. While the player can usually reskin their character, the overall appearance and the meaning of the avatars’ actions are not of particular importance.

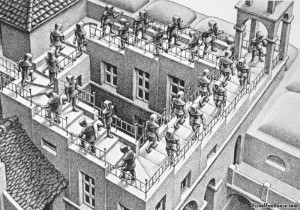

Above: possibly the greatest moment in video game history. Insane amount of technical skill required to a) block Chun-Li’s fearsome kicks and b) come back and win the game.

Above: if the first video was Bach’s Cello Suite No. 1 Prelude in G Major, then this is Lil Wayne’s “A Milli”: equally incredible, significantly more crass. NSFW language.

Now, in third-person and first-person narrative-based roleplaying games, much more emphasis is placed on the body image than the schema. The character on screen, whether playing as Geralt in the Witcher series or Jack in Bioshock, is an extension of your body, and the choices made within that virtual body are identifiable with those of your body. For example, in the Bioshock games, the player is presented with the dilemma of Little Sisters—genetically mutated children who harvest a substance known as ADAM (essentially, potent stem cells) from the dead bodies that are scattered around Rapture, a failed Objectivist undersea city-society (I know, right?). The player can either cure them by injecting a serum into them that cures them of their mutation, or they can kill them and harvest their ADAM reserves (because this functions as currency for superpowers and the like in-game). Now, regardless of what you choose, the game is first-person, and the player witnesses the choices made through the interface played out on screen. This presents the issue of “well, would I do this in this situation? Would I physically perform these actions?”, and it is this issue that gives many players pause the first time these games. In The Witcher, the player embodies Geralt, a monster hunter with what essentially amounts to no defined moral code. The player is often put into situations where they are presented with a set of choices, usually during dialogue, where there is no clear-cut right answer. In this sense, the player must reflect upon their body image and what they could picture themselves actually doing in such a situation.