I wanted to follow up on Alfredo’s and Cuillen’s questions from class today in more depth, especially since both questions help expand our digital literacy.

Alfredo asked if Fair Use covered footage from a film used as a transition. We know from our Fair Use discussion today that an image that is central to analysis is most firmly protected by the “purpose of the use” pillar of Fair Use. But I think our discussion did not explain how what I call “b-roll” footage is central to analysis. The explanation of why is an important exploration in composition and digital rhetoric, so I want to thank Alfredo for introducing this nuance as a problem for our class project.

“B-roll” is a term from documentary film-making. Anthony Artis explains in more detail below, in this snippet of “Your B-roll is your A-roll“:

“The term ‘B-roll’ comes from the world of film where editors used to use an “A” and a “B” roll of identical footage, before the digital age changed everything. B-roll shots are similar to cutaways in that they help break up the static interview shots, but B-roll plays a more major role in telling a visual documentary story.

A long-time documentary filmmaker I know actually refuses to use the term B-roll, because she feels it diminishes the importance of these visuals—and she’s right. B-roll should not be a secondary or low priority. It really should be thought of as “A-roll,” because it is the action of your story, which serves to reveal character. Without it, you’ve just got a bunch of talking heads… booor-ing.

Even with an engaging storyteller speaking, the audience still needs to see visuals of the scene, settings, characters, and action of the story. An interview or voice-over itself is the narration or literal telling of the story. The B-roll is the showing of the story. Together they can complement each other by painting a more complete picture. That amazing guitarist could tell us what it was like to play Woodstock (the real one), but we’ve only got half the story until we cut in the B-roll shots that show the multitudes of free-spirited, mud-covered hippies swirling to the music as far as the camera lens can see. A soldier could tell us what it’s like to be in combat, but when we cut in a shot of explosions and a chaotic firefight, his story takes on real human meaning. Now we’ve got a much stronger sense of story than either an interview or B-roll footage alone could have given us.”

Think about how your B-roll is functioning in a video essay. Like Alfredo says (and I think he’s absolutely right which is why I bothered to go and watch a couple video essays with his question in mind at 9:45 on a Tuesday night), tons of video essays use film clips and secondary sources as transitional material. It works like the illustrative material that Artis is calling “B-roll”. Here’s the big exception to how you’re using your B-roll and how a documentary film maker uses their B-roll (i.e. why the documentary filmmaker can’t claim Fair Use). You’re flipping to B-roll when you want to show a bunch of examples of what you’re talking about at once (sort of like a mini-supercut) or when you’re showing a secondary source. Then you’re cutting back to the big scene you’re analyzing for your “A-roll”. Both A and B are functioning together to “paint a more complete [analytical] picture”. By this construction, you’re pairing an analytical claim (“Film does this…”) with visual examples. Then you’re using a single sustained example to make a more localized claim. Your video essay, if it imitates what we’ve watched, does some version of this swap several times–between A-roll and B-roll.

If your B-roll is neither

a) evidence for your claim nor

b) a secondary source you are bringing into your conversation

then it is likely not covered under Fair Use. Source material you use for this purpose from databases of material with the appropriate Creative Commons license for your use.

The video essays that have survived copyright strikes do so because they understand this distinction. We will talk about this in class more on Thursday. If you’re looking for transitional footage that is not covered under Fair Use, here is a great resource guide for how to find it. The video below explains Creative Commons in 3 minutes! Check it out.

Watch how Lewis Bond uses A-roll, B-roll, and transitional material (gathered from Creative Commons) when he discusses film composition–or choose your own favorite video essayist and do this same analysis for the first 5 minutes of the author’s argument. We’ll dissect this example in class on Thursday. (P.S. Turn on the CC and you’ll see how Lewis Bond gives credit for his primary sources.)

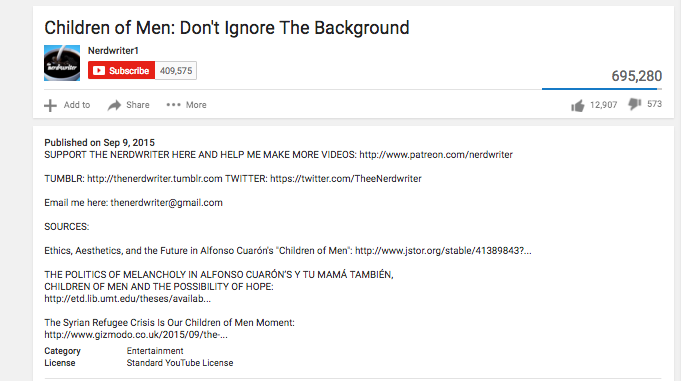

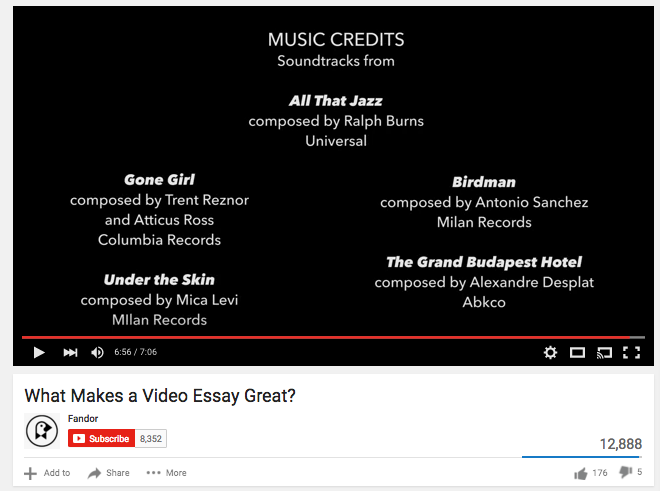

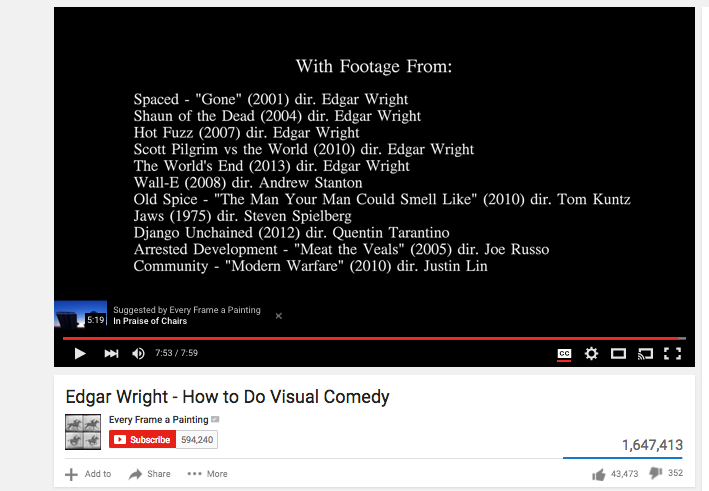

Cuillen asked how to cite sources in the video essay itself. Here’s some screenshots that show different strategies.

In the video info, like NerdWriter:

Image Source: Nerdwriter

Giving your film “credits” (Kevin B. Lee, Tony Zhou)

Image Source: Fandor

Image source: Every Frame a Painting

I’ve also seen people put citations in as annotations, but I like that less because most people turn annotations off. (It’s also a pain to do.)