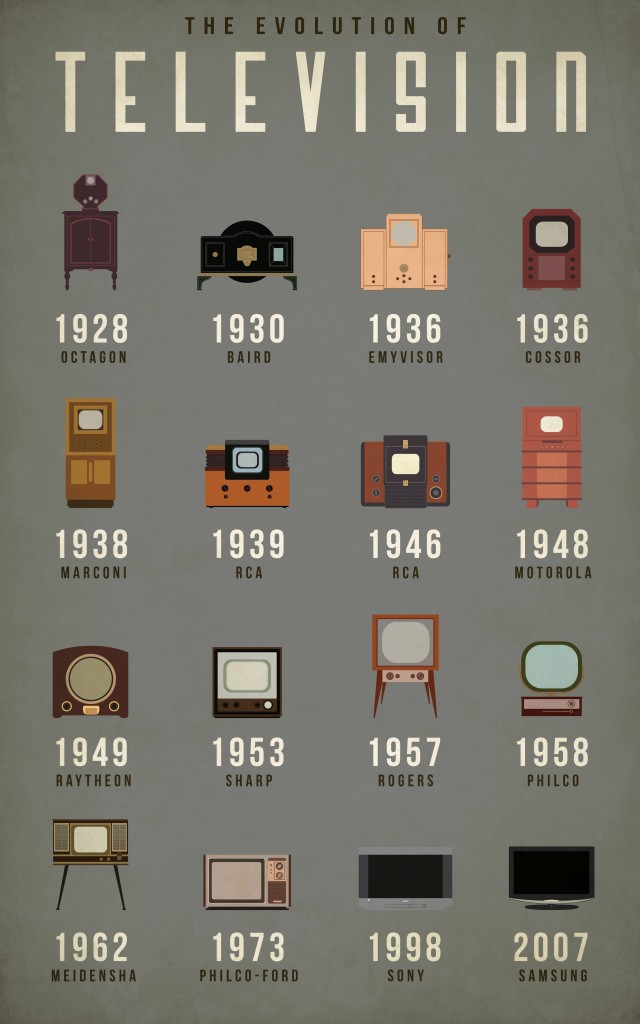

The main focus of our transition from the second unit to the third unit of our class appears to be what constitutes the New Media, how it functions, and how it affects us. In Lev Manovich’s essay “New Media from Borges to HTML,” the author explores the character of New Media and offers a variety of definitions for it based on its function and its history. YouTube is a unique and nuanced platform that functions as emblematic of New Media, with a recursive nature that encourages community-building and interaction with previously created media.

YouTube, as outlined in William Uricchio’s essay “The Future of a Medium Once Known as Television,” appears to fulfill Manovich’s proposition of New Media as “metamedia” in an interesting way (Manovich 20). YouTube is a chimerical beast that interacts with traditional media such as television and film, while remaining distinctively outside of them, primarily by “[seizing] the periphery, providing access to the scene even more consistently than to the films (or television shows) themselves” (Uricchio 30). YouTube is a haven more for videos and content that are about the source (whether filmic, related to television, or games) than the source itself, even if someone were to create an original short film or series of episodes.

In the Manovich essay, he theorizes that “the new avant-garde is no longer concerned with seeing or representing the world in new ways but rather with accessing and using in new ways previously accumulated media” (Manovich 23). This is why one can see a single, original work spawn an extremely high number of “periphery” content, ranging from reaction videos to remixes to video essays to simple text-based comments. YouTube appears to be a haven for the postmodern act of “reworking already existing content, idioms, and style, rather than genially creating new ones” (23).

Uricchio claims that YouTube “misses the capacity for televisual liveness,” meaning (I believe) that since the platform is reliant on the “publishing” of content, which means that once the content is created and put onto the platform, it remains there, forever accessible (Uricchio 32). This function facilitates the recursive creation of content from other content, since these artifacts can be found if one knows how to search for them, thus fulfilling this qualification to be considered New Media according to Manovich (of course, his qualifications are more descriptive than prescriptive).

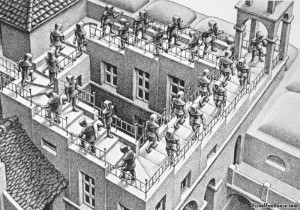

What makes YouTube a particularly fascinating platform is that this act of recursively creating content from other content opens up a discourse on a subject that had, up until the commercialization of the personal computer, not experienced the same degree of freedom it has today. There has always been a sense of community-building in the manner with which individuals interact with content and create content based off of it (consider, for example, fan letters and theories in reaction to Golden Age science fiction periodicals), which has certain implications for the postmodern movement if it is to be considered as emblematic of it. Perhaps the postmodern act of “using in new ways previously accumulated media” is an act of identification rhetoric: by interacting with old media and others who interact with the same media and perform generative acts of content-creation, communities are built. Just a thought though.